Audit and Evaluation Branch

Natural Resources Canada

February 28, 2025

On this page

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Relevance

- Effectiveness

- Efficiency

- Lessons learned

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix A: Funding and support programs in other countries

- Appendix B: Case Studies

- Appendix C: Other Funding Programs in Canada

- Appendix D: Evaluation Team

List of acronyms

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AEB

- Audit and Evaluation Branch

- CES

- Canadian Energy Strategy

- CIB

- Canadian Infrastructure Bank

- DEEP

- Deep Earth Energy Production

- DERs

- Distributed Energy Resources

- DG

- Director General

- EDI

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- EETS

- Energy Efficiency and Technology Sector

- ERPP

- Emerging Renewable Power Program

- ESS

- Energy Systems Sector

- EWG

- Evaluation Working Group

- FTEs

- Full-time equivalents

- GBA+

- Gender-based Analysis Plus

- G&C

- Grants and contributions

- GC

- Government of Canada

- GHG

- Greenhouse gas

- GI

- Green Infrastructure

- IDEA

- Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility

- KI

- Key informant

- MT

- Megatonne

- MW

- Megawatts

- NRCan

- Natural Resources Canada

- OERD

- Office of Energy Research and Development

- PCF

- Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change

- REAs

- Regional Environmental Assessments

- REED

- Renewable and Electrical Energy Division

- RERAs

- Regional Energy Resource Assessments

- SGG

- Smart Grid Grants

- SGP

- Smart Grid Program

- SREPs

- Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program

- TB

- Treasury Board

- TRL

- Technology Readiness Level

- US

- United States

Executive summary

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the Evaluation of the Smart Grid Program (SGP) and the Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP). This evaluation responds to a commitment to the Treasury Board (TB) and a requirement from Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The SGP is a $100 million, five-year program that provides funding to the deployment of proven smart grid integrated systems (n = 10), larger-scale demonstrations of near-commercial smart grid technologies (n = 6), and hybrid projects (n = 6) that include both demonstration and deployment components. The program’s intent is to accelerate the shift to a clean growth economy by optimizing electricity assets, boosting renewable generation, and enhancing power system reliability, resiliency, and flexibility while maintaining cybersecurity.

The ERPP is a $200 million, eight-year program that supports large deployment projects (n = 6) and studies (n = 9). Deployment projects introduce new renewable power technologies to Canada. Studies generally intend to advance knowledge and disseminate information relevant to potential emerging renewable power projects. The ERPP intends to expand the portfolio of commercially viable renewable energy sources in provinces and territories to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from their electricity sectors by mitigating risks and challenges associated with emerging renewable energy projects in Canada.

The evaluation of the SGP and ERPP focused on: (1) the continued need for public investment in smart grids and renewable energy technologies (relevance); (2) the programs’ achievement of the immediate and intermediate outcomes (effectiveness); (3) the programs’ design, implementation, and capacity to operate as planned to achieve and report on the intended outcomes (efficiency); and (4) identifying key aspects from the implementation of the two programs that should be brought forward (lessons learned). The period covered by the evaluation was fiscal years 2018-19 to 2022-23. The approach and methodology used for the evaluation followed the TB Policy on Results (2016) and related Standards on Evaluation.

What the evaluation found

Overall: The evaluation found that the SGP and ERPP are relevant and will continue to be relevant as Canada works towards its climate change targets. For the most part, the programs are being delivered efficiently. While these two programs have achieved meaningful progress and achievement of many of their intended short- and medium-term outcomes, there are areas of improvement and lessons learned to ensure that the SGP and ERPP, along with similar programs, continue to make the utmost progress towards medium-term outcomes and long-term outcomes.

Relevance: The SGP and ERPP are relevant. The SGP and ERPP, or similar programming, are important to help Canada meet its climate change targets. The programs align with the Government of Canada priorities and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) strategic outcomes related to clean energy and climate change. The programs also complement other programs and initiatives that are part of a larger ecosystem working towards a clean growth economy and clean energy in Canada. The SGP and ERPP help the utilities sector to overcome key barriers in the transition towards clean energy systems. There is evidence that the smart grid and emerging renewable energy projects were largely enabled because of the federal government support.

Effectiveness: The SGP and ERPP have been effective in achieving their immediate outcomes and some of their intermediate outcomes. However, some intermediate outcomes are still in progress (e.g., “Canadian smart grid sector growth and innovation” for the SGP and “emerging renewable projects contributing to electricity grid” for the ERPP) and related targets are unlikely to be achieved. There is also limited information to determine progress for several indicators during the evaluation period. While the programs showed some progress towards the long-term outcomes and ultimate outcome, program impact may be limited by the programs’ limited scale and the extensive scope of the challenge (i.e., achieving net-zero emissions in Canada's electricity sector). A number of positive unintended outcomes and one negative unintended outcome were identified. The high level of program flexibility, professionalism of the NRCan program staff, and widespread dissemination of program information and results are key to program success. Notably, there is an interest in furthering the dissemination of program information and results. Regulatory barriers, technological issues due to innovation, and the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by projects have negatively affected program implementation and outcome achievement. There is a continued need for NRCan to provide support in examining and understanding the impact of business models and regulatory environments on project success, as projects under both programs continue to face regulatory barriers.

Efficiency: The SGP and ERPP have generally been designed efficiently. Their design reflects that used in a similar program being implemented in other countries (e.g., the United States [the US], Australia). The flexibility of the program design and NRCan program delivery staff have been key factors in the programs’ success. While the SGP’s “one window” approach provided the opportunity for the program to fund a greater range of projects, hybrid projects faced many administrative burdens. Although many of the program’s positive elements were implemented, the programs encountered deviations from their original plans (e.g., project time extensions and supporting additional funding requests) because of the need to adapt to the changing circumstances.

Although both programs have a performance measurement approach in place, there are inconsistencies in how the programs collect performance information. The lack of a consistent approach in how data (such as job year) were reported rendered it impossible to aggregate the results, and thus accurately assess the extent to which some of the indicators have been met. Additionally, the deployment stream of the programs stopped collecting certain performance metrics (e.g., GHG emissions reductions) throughout the project duration. These metrics will only be collected in final reporting, as those responsible for program delivery only expect meaningful data to be available once solutions have been fully implemented and tested. At that time, evidence suggests it will most likely be too difficult and too late to identify weaknesses or errors, and make changes and corrections at the project- and program-level. Removing annual reporting increases the risk of poor-quality performance information. The programs recognized this and have already begun implementing related improvements.

The programs and NRCan have continuously improved their activities around Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), including selection of projects with Indigenous involvement and a better integration of GBA+ and EDI considerations in the Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program (a newer program that, in some way, replaces the SGP and ERPP).

Lessons learned: Evidence indicated that there are lessons learned to bring forward for the SGP, ERPP, and similar programming. These lessons learned encompassed processes, program design, and communication and engagement strategies that the programs and NRCan could consider going forward.

Recommendations and management response and action plan

| Recommendations | Management Response and Action Plan |

|---|---|

|

Management Response: Management agrees. The ADM ESS, in collaboration with ADM EETS where appropriate, will continue to proactively work with other levels of government to develop strategies to better understand and share information, lessons, and analysis on the impact of business models and regulatory environments on project success and scale up of energy technologies, in order to help inform stakeholder decision-making and recommendations. Ongoing collaboration with the Canadian Infrastructure Bank (CIB) is helping our programs identify additional risks within business models for potential projects. The Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways (SREPs) program, the extension of the Smart Grid Deployment Program and the ERPP, is currently finalizing a Memorandum of Understanding with the CIB to work more closely on these issues. Position responsible: Director General (DG) of the Energy Resources Branch and DG of the Office of Energy Research and Development (OERD) Timing: September 2025 |

|

Management Response: Management agrees, where appropriate. In response to Recommendation #2, improved calculations for job creation are currently being finalized. The ERPP and SREPs program will be seeking standardized job creation information in their quarterly reporting requirements to ensure recipients are reporting on job creation in real time. Standardized templates are currently being updated and translated and should be ready to provide to recipients with existing agreements in the next quarterly reporting. To meet existing reporting commitments and targets, energy research, development, and demonstration programs will continue to collect annual data on job years of employment, as well as request the number of new jobs. Where department-wide approaches enable better and more coordinated data sharing across all sectors, the OERD will work with align with those approaches. These programs were intended to focus on experimentation, generating important lessons learned, rather than job creation. Going forward, ESS-REED and EETS-OERD will collaborate with NRCan’s Planning, Delivery and Results Branch and Audit and Evaluation Branch to ensure that outcomes, indicators and results information focus on the intended purpose of the program(s). ESS and EETS agree that for any future hybrid programs or projects, sectors will better harmonize approaches to data collection, while still ensuring compliance with requirement under the Term and Conditions for each program stream. Position responsible: Senior Director the Renewable and Electrical Energy Division (REED) and DG OERD Timing: December 2024 |

|

Management Response: Management agrees. In response to Recommendation #3, knowledge dissemination of program and project results will be available on the program websites at the completion of the project, with the permission from the recipients. Where projects are withdrawn, programs will be unable to post project results. Not all information can be shared for deployment projects due to commercial sensitivities. Funding recipients often present at national and international conferences and panels as leaders in their fields. However, where information is not commercially sensitive, and value can be gained from broader dissemination, EETS-OERD will continue to undertake knowledge sharing activities (publications, presentations, workshops etc.) as resources permit in a timely and strategic manner to amplify and facilitate funding and non-funding supports. Position responsible: Senior Director REED and DG OERD Timing: March 2028 |

Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the evaluation of Natural Resource Canada’s (NRCan’s) Smart Grid Program (SGP) and Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP). The Audit and Evaluation Branch (AEB) conducted this evaluation as part of the NRCan Integrated Audit and Evaluation Plan 2022-27. This evaluation responds to a commitment to the Treasury Board (TB) and a requirement per Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation examined the SGP and ERPP’s relevance (i.e., continued need, alignment with priorities, and appropriateness of the federal role) and performance (i.e., effectiveness, efficiency, and economy), per the Policy on Results (2016). The evaluation aimed to add value and inform future NRCan programming.

Program profile

Program context and rationale

In 2016, Canada ratified the Paris Agreement with a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 30% from 2005 levels by 2030. The Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, passed into law in 2021, furthers this commitment by enshrining in legislation Canada's commitment to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. For Canada to meet the 2030 target and net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, additional mitigation measures are required at all levels of government, as well as by the private sector and individual Canadians.

In July 2015, Premiers of Canada finalized the Canadian Energy Strategy (CES) to enable a cooperative approach to sustainable energy development in Canada. In 2016, the CES collaboration between provinces and territories grew to include the participation of the GC in some areas of CES work, including clean energy technology and innovation.

In 2016, the Government of Canada (GC) released the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF). Developed with provinces and territories and in consultation with Indigenous peoples, the PCF outlines strategies and steps aimed at achieving reduction in carbon pollution across all sectors of the economy, driving innovation and growth through supporting technology development and adoption and increasing Canadian competitiveness in the global low-carbon economy.

In an effort to fulfil key commitments under the PCF and the CES, NRCan received over $800 million beginning in fiscal year 2018-19 to deliver five national programs under the Green Infrastructure (GI) envelope of the Investing in Canada Plan. The GI envelope includes the SGP ($100 million) and ERPP ($200 million). The SGP and ERPP focus on smart electrical grids and renewable energy sources, which are key elements to combat climate change. These technologies and infrastructure have the potential to reduce GHG emissions and assist Canada’s goal of achieving 90% non-emitting electricity generation by 2030. However, the utilities sector faces unique challenges in pursuing smart grid deployments and demonstrations due to regulatory and financial constraints. Market and regulatory barriers have also prevented the commercial deployment of emerging renewable electricity technologies in Canada, although these technologies have been successfully deployed abroad.

Program descriptions

Smart Grid Program (SGP)

NRCan introduced the SGP to support the modernization of the electricity grid required to meet commitments made under the PCF. Up to $100 million was invested in the five-year program under Budget 2017 to fund smart grid systems. Smart grids are intended to make better use of existing energy infrastructure, increase energy efficiency, and promote innovation (e.g., generation, transmission, and distribution assets). The ultimate objective of smart grids is to ensure more secure delivery of electricity to consumers, and thereby provide higher quality electricity service to Canadians.

Smart grids utilize digital and advanced technologies, such as smart meters, sensors, and automation, to balance electricity supply and demand. Smart grids contribute to GHG mitigation by boosting the hosting capacity of renewable energy, increasing electricity system resiliency, and improving system efficiency and conservation.

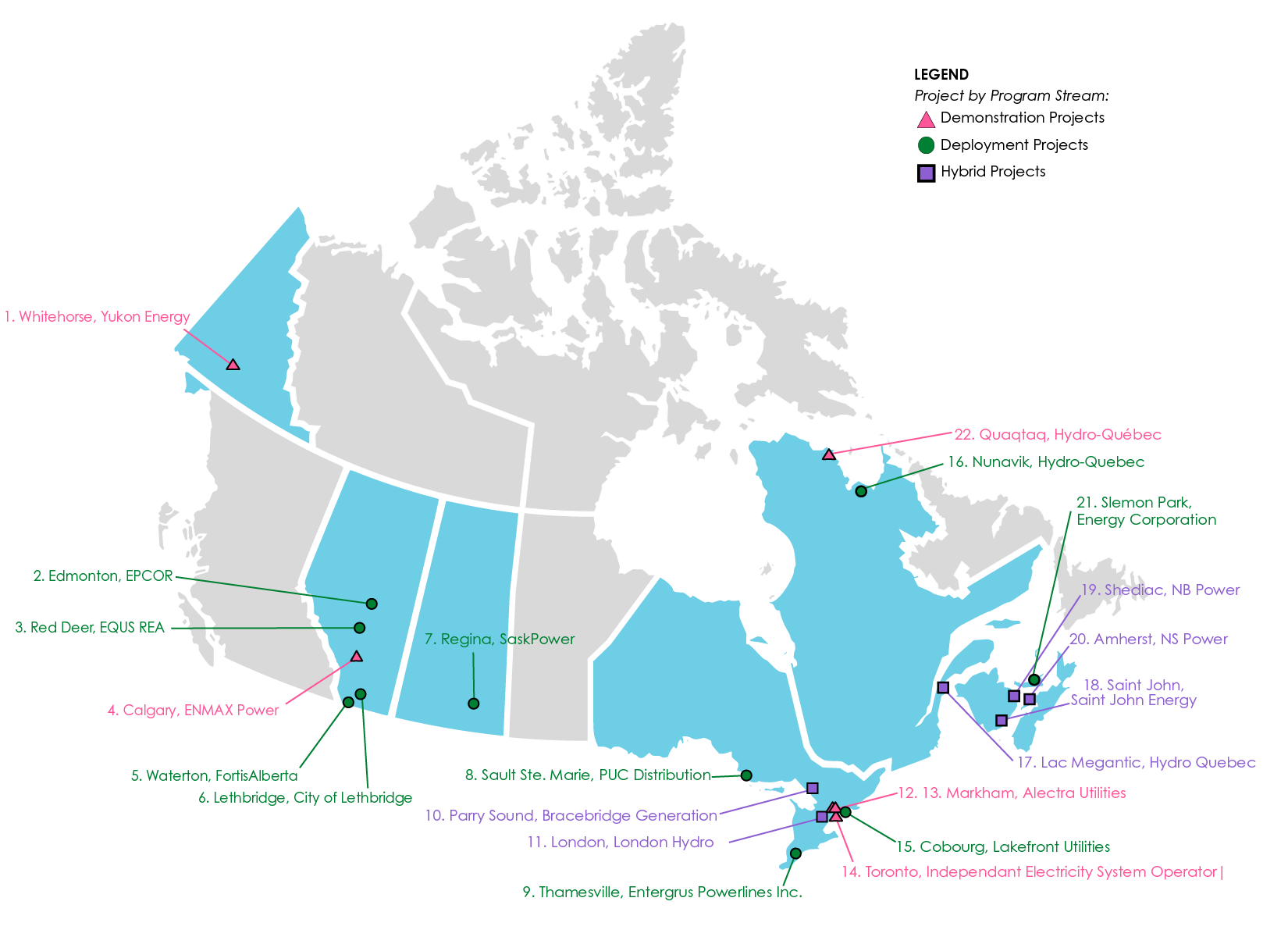

The SGP supports larger-scale demonstrations of near-commercial smart grid technologies in addition to deployment of proven smart grid integrated systems. The SGP also supports hybrid projects, which include both demonstration and deployment components. A total of 24 projects were supported, including 10 deployment projects, six demonstration projects, six hybrid projects, and two cancelled projects (see Figure 1 for the list of projects that proceeded to completion). Eligible recipients for the SGP include legal Canadian entities, electricity utilities, system operators, transmission owners and operators, and provincial, territorial, regional, and municipal governments.

Figure 1: Smart Grid Program projects (n = 22)

Text version

Figure one: A map showing 22 SGP projects located in Canada.

Yukon

- One demonstration project: Whitehorse, Yukon Energy.

Alberta

- One demonstration project: Calgary, ENMAX Power.

- Four deployment projects: Edmonton, EPCOR; Red Deer, EQUS REA; Waterton, FortisAlberta; Lethbridge, City of Lethbridge.

Saskatchewan

- One deployment project: Regina, SaskPower.

Ontario

- Three demonstration projects: Markham, Alectra Utilities; Markham, Alectra Utilities; Toronto, Independent Electricity System Operator.

- Three deployment projects: Sault Ste. Marie, PUC Distribution; Thamesville, Entergrus Powerlines Inc.; Cobourg, Lakefront Utilities.

- Two hybrid projects: Parry Sound, Bracebridge Generation; London, London Hydro.

Quebec

- One demonstration project: Quataq, Hydro-Quebec.

- One deployment project: Nunavik, Hydro-Quebec.

- One hybrid project: Lac Megantic, Hydro-Quebec.

New Brunswick

- Two hybrid projects: Shediac, NB Power; Saint John, Saint John Energy.

Prince Edward Island

- One deployment project: Slemon Park, Energy Corporation.

Nova Scotia

- One hybrid project: Amherst, NS Power.

Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP)

In 2018, NRCan announced the launch of a $200 million expression of interest for the ERPP, targeting the expansion of renewable energy sources to assist provinces and territories in reducing GHG emissions in the electricity sector. This eight-year funding is intended to support efforts to expand viable renewable energy technologies.

Renewable energy sources, like solar, wind, and geothermal, play a key role in mitigating GHG emissions, primarily through their low-to-zero operational emissions. Additionally, the decentralization of energy production, enabled by renewables, can lead to more resilient and efficient energy systems.

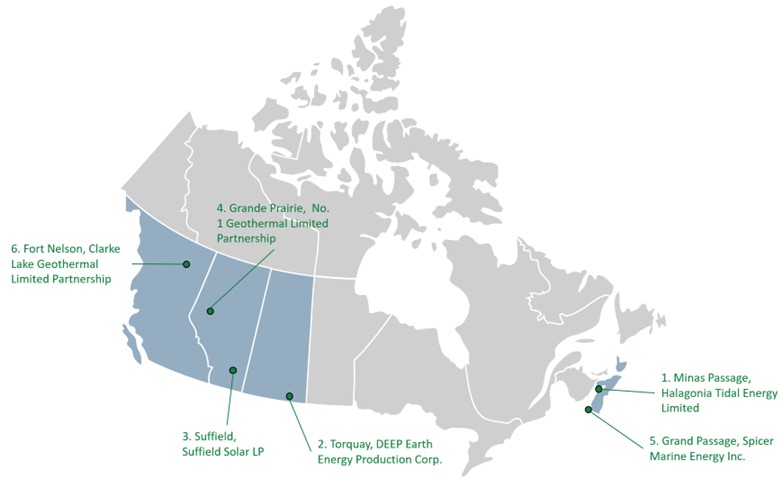

This program is designed to mitigate risks and challenges associated with emerging renewable energy projects. The anticipated outcome of the ERPP is that emerging renewable power will play a more important role in Canada’s electricity supply. The ERPP funds large deployment projects and small, focused studies; a total of 15 initiatives were supported (see Figure 2 for the list of deployment projects and Table 1 for the list of studies). The deployment component supports the establishment of new industries in Canada through the introduction of renewable power technologies that are established commercially outside Canada or demonstrated but not yet deployed in Canada. The studies aim to evaluate the viability of a planned emerging renewable power project in a specific region; coordinate projects among several stakeholders; monitor environmental effects of a project; or study the impacts of current electricity system practices in specific areas. Eligible recipients for the ERPP include legal Canadian organizations (for-profit or not-for-profit) and provincial, territorial, regional, and municipal governments.

Figure 2: Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP) deployment projects (n = 6)Footnote 1

Text version

Figure two: A map showing 6 ERPP deployment projects located in Canada.

Nova Scotia – two projects:

- Minas Passage, Halagonia Tidal Energy Limited

- Grand Passage, Spicer Marine Energy Inc.

Saskatchewan – one project:

- Torquay, DEEP Earth Energy Production Corp.

Alberta – two projects:

- Grande Prairie, No. 1 Geothermal Limited Partnership

- Suffield, Suffield Solar LP.

British Columbia – one project:

- Fort Nelson, Clarke Lake Geothermal Limited Partnership

| Company | Project Name | Region |

|---|---|---|

|

AB/BC Intertie Restoration Study | Alberta-British Columbia |

|

Electricity Sector Regulatory Efficiency Review | National (Ontario office) |

|

SaskPower / Manitoba Hydro Regional Coordination Study | Saskatchewan-Manitoba |

|

Initiative de modélisation énergétique: apporter les outils nécessaires pour appuyer la transition énergétique du Canada | National (Québec office) |

|

Pathway Program | Nova Scotia |

|

Atlantic Clean Power Roadmap Planning | Atlantic (Nova Scotia office) |

|

Risk Assessment Program for Tidal Stream Energy | Nova Scotia |

|

Geothermal resources associated with crustal-scale fault systems in Canada | Yukon |

|

Guidance for Policy-Makers: Waterpower’s Value and Potential in Canada | National |

Governance

The SGP is in the purview of the Energy Systems Sector (ESS)’s Renewable and Electrical Energy Division (REED) for its deployment component and the Energy Efficiency and Technology Sector (EETS)’s Office of Energy Research and Development (OERD) for its demonstration component. The ERPP is in the purview of the ESS. The OERD and REED work jointly on the SGP hybrid projects. Each of these two NRCan sectors is led by an Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM), serving as functional leads, who are ultimately accountable for the successful delivery of the programs.

For each program, proposals are reviewed by a core team against the mandatory criteria stated in the program’s Terms and Conditions. The proposals are then evaluated by a Technical Review Committee of subject-matter experts, from which a recommended list of projects is created and presented to the program Director, and then endorsed by the Director General (DG) of the Science and Technology (S&T) committee. The list of recommended projects is finalized with the ADM approval. A B-list of projects is also established to use as needed if approved projects cannot go ahead.

Programs’ expected results

In NRCan’s Departmental Results Framework, the SGP and ERPP fall under the: (1) Electricity Resources Program and (2) Energy Innovation and Clean Technology Program; and within the Core Responsibility 2: Innovative and Sustainable Natural Resources Development. A single SGP and ERPP logic model (Figure 3) was developed by the evaluation team as part of the evaluation planning process, leveraging material from REED and OERD. The logic model was reviewed and approved by the Evaluation Working Group (EWG).Footnote 2 The logic model summarizes the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes developed at the outset of the SGP and ERPP.

Figure 3: Smart Grid Program (SGP) and Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP) Logic Model

| Ultimate outcome | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provide Canadians with access to safe, resilient, reliable, affordable, and non-emitting energy, leading to net-zero emissions in the electricity sector. | |||||||||||||

Long-term outcomes (10+ years) |

|||||||||||||

| SGP | ERPP | ||||||||||||

| Environmental benefits from smart grid development and deployment. | Economic benefits from smart grid projects. | Expanded portfolio of commercially viable renewable energy technologies available in Canada. | Establishment of new industries and supply chains. | ||||||||||

Intermediate outcomes (3 – 10 years) |

|||||||||||||

| Demonstration projects move emerging technologies closer to commercial readiness. | Increased number of commercially ready smart grid integrated systems from the demonstration program. | Canadian smart grid sector growth and innovation. | Larger [5 Megawatts (MW+)] emerging renewable power projects enabled by program. | Emerging renewable projects contributing to electricity grid. | Increased employment in emerging renewables. | ||||||||

| Improved environmental performance through GHG reductions of Canadian electricity sector. | Increased investment by stakeholders in emerging renewable projects. | ||||||||||||

Immediate outcomes (1 – 3 years) |

|||||||||||||

| Increased development and deployment of smart grid capabilities in Canada. | Increased investment by stakeholders in smart grid technology demonstration and deployment projects. | Increased Canadian smart grid sector innovation. | Smaller (2-5 MW) emerging renewable power projects enabled by the program. | Larger portfolio of renewable energy technologies ready for commercialization in Canada. | Increased support by provinces for emerging renewable power deployment projects. | ||||||||

| SGP | ERPP | ||||||||||||

Outputs |

|||||||||||||

| Implementation of non-emitting energy and grid modernization projects. | Analysis and reporting on collected project data. | ||||||||||||

Activities |

|||||||||||||

| Stakeholder engagement, including provincial and territorial governments, sector and industry associations, and potential project proponents. | Call for, review, and approve potential projects related to smart grids and emerging renewable power. | Monitor projects and collect and assess project data. | Provide evidence-based decisions and policy advice to NRCan senior decision-makers. | ||||||||||

Inputs |

|||||||||||||

| Funding | Time | Staff expertise | Government mandates | Leadership | Stakeholder feedback | Access to research | Information | ||||||

Table description

Figure three: The program logic model for the SGP and ERPP illustrates the connections from inputs to activities, outputs, and outcomes.

The inputs are: Funding, time, staff expertise, government mandates, leadership, stakeholder feedback, access to research, and information.

Both programs’ activities are:

- Stakeholder engagement, including provincial and territorial governments, sector and industry associations, and potential project proponents.

- Call for, review, and approve potential projects related to smart grids and emerging renewable power.

- Monitor projects and collect and assess project data.

- Provide evidence-based decisions and policy advice to NRCan senior decision-makers.

Both programs’ outputs are:

- Implementation of non-emitting energy and grid modernization projects.

- Analysis and reporting on collected project data.

SGP immediate outcomes (1 to 3 years) are:

- Increased development and deployment of smart grid capabilities in Canada.

- Increased investment by stakeholders in smart grid technology demonstration and deployment projects.

- Increased Canadian smart grid sector innovation.

ERPP immediate outcomes (1 to 3 years) are:

- Smaller (2-5 MW) emerging renewable power projects enabled by the program.

- Larger portfolio of renewable energy technologies ready for commercialization in Canada.

- Increased support by provinces for emerging renewable power deployment projects.

SGP intermediate outcomes (3 to 10 years) are:

- Demonstration projects move emerging technologies closer to commercial readiness.

- Increased number of commercially ready smart grid integrated systems from the demonstration program.

- Canadian smart grid sector growth and innovation.

ERPP intermediate outcomes (3 to 10 years are):

- Larger [5 Megawatts (MW+)] emerging renewable power projects enabled by program.

- Emerging renewable projects contributing to electricity grid.

- Increased employment in emerging renewables.

- Improved environmental performance through GHG reductions of Canadian electricity sector.

- Increased investment by stakeholders in emerging renewable projects.

SGP long-term outcomes (10+ years) are:

- Environmental benefits from smart grid development and deployment.

- Economic benefits from smart grid projects.

ERPP long-term outcomes (10+ years) are:

- Expanded portfolio of commercially viable renewable energy technologies available in Canada.

- Establishment of new industries and supply chains.

Both programs’ ultimate outcomes are:

- Provide Canadians with access to safe, resilient, reliable, affordable, and non-emitting energy, leading to net-zero emissions in the electricity sector.

Program resources

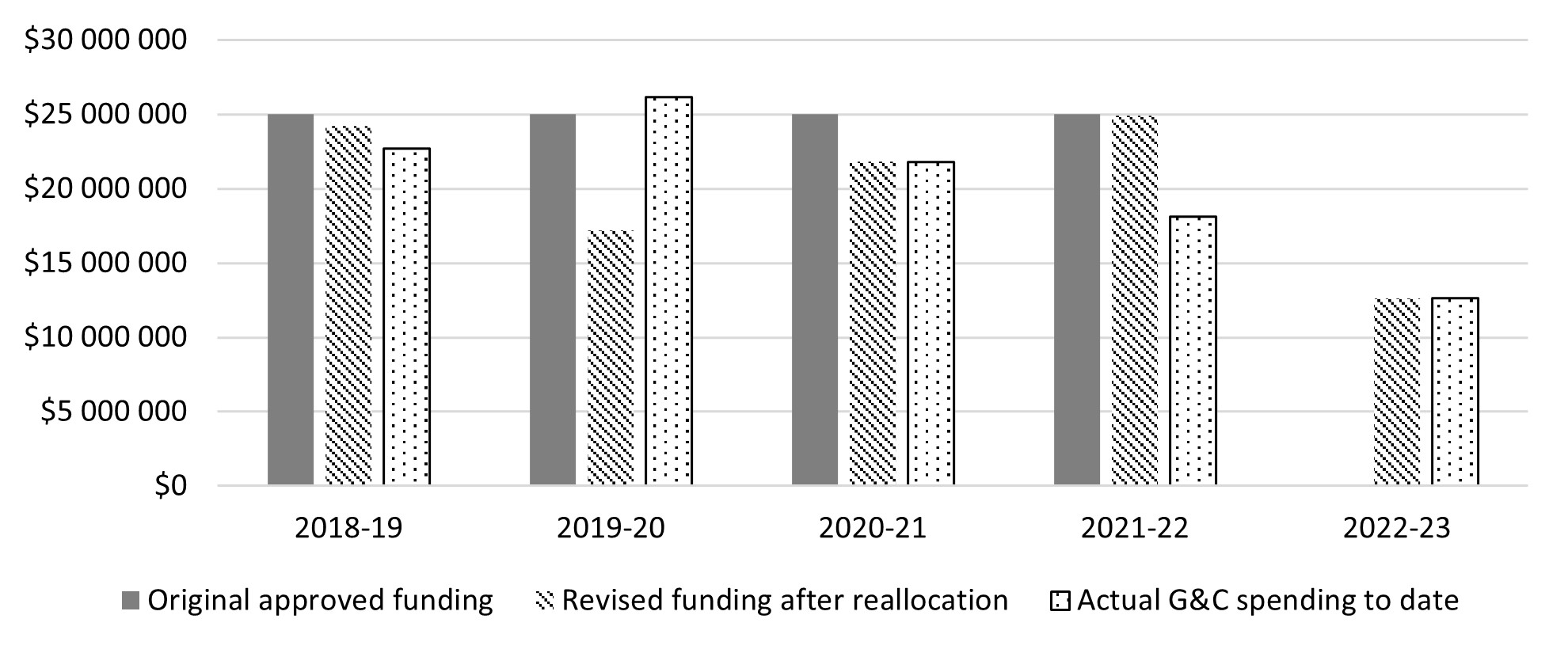

The SGP was originally allocated $100 million over four years. Due to delays related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the SGP was extended to five years (2018-19 to 2022-23). Its budget was also increased slightly, to $101.38 M. Figure 4 shows the original and revised budgets for the SGP, as well as actual dollars spent up to fiscal year 2022-23. The amounts include all fundings (i.e., salaries, operations, and contributions). At program close in 2022-23, the SGP had spent its entire budget allocation.

Figure 4: NRCan funding for the Smart Grid Program (SGP), original, revised, and actual amounts, by fiscal year

Text version

Figure four: A chart with vertical bars that provides (in Canadian dollars) the original approved funding, revised funding after reallocation, and actual G&C spending to date by fiscal year for the SGP.

| Original approved funding | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $25.0 million |

| 2019-20 | $25.0 million |

| 2020-21 | $25.0 million |

| 2021-22 | $25.0 million |

| 2022-23 | - |

| Revised funding after reallocation | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $24.2 million |

| 2019-20 | $17.2 million |

| 2020-21 | $21.8 million |

| 2021-22 | $24.9 million |

| 2022-23 | $12.6 million |

| Actual G&C spending to date | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $22.7 million |

| 2019-20 | $26.2 million |

| 2020-21 | $21.8 million |

| 2021-22 | $18.1 million |

| 2022-23 | $12.6 million |

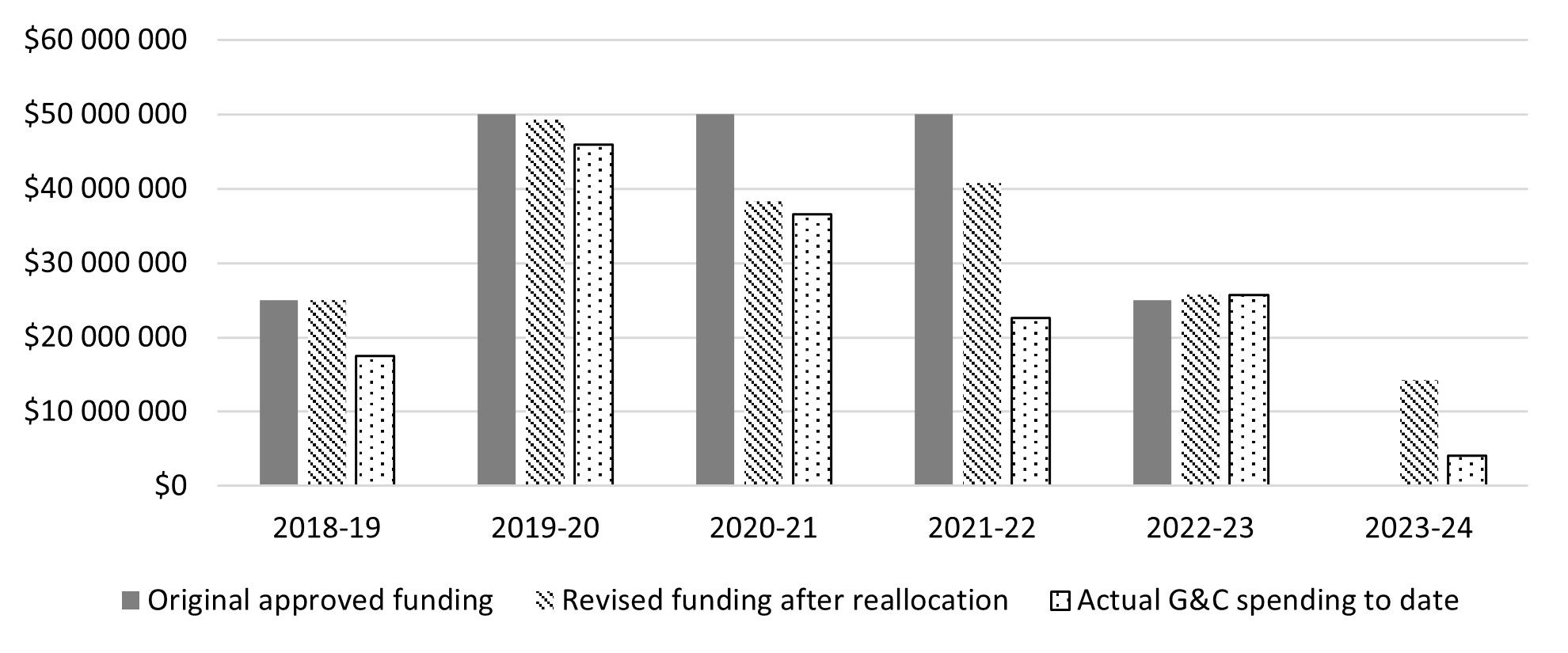

The ERPP was allocated $200 million over five years. Due to COVID delays, it was also extended to eight years (2018-19 to 2025-26). Figures 5 shows the original and revised budgets for the ERPP, as well as actual dollars spent up to fiscal year 2023-24. The ERPP has almost $48 million to spend in Grants and Contributions over the final two years of the program.

Figure 5: NRCan funding for the Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP), original, revised, and actual amounts, by fiscal year

Text version

Figure five: A chart with vertical bars that provides (in Canadian dollars) the original approved funding, revised funding after reallocation, and actual G&C spending to date by fiscal year for the ERPP.

| Original approved funding | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $25.0 million |

| 2019-20 | $50.0 million |

| 2020-21 | $50.0 million |

| 2021-22 | $50.0 million |

| 2022-23 | $25.0 million |

| 2023-24 | - |

| Revised funding after reallocation | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $25.0 million |

| 2019-20 | $49.2 million |

| 2020-21 | $38.4 million |

| 2021-22 | $40.7 million |

| 2022-23 | $25.7 million |

| 2023-24 | $14.2 million |

| Actual G&C spending to date | |

|---|---|

| 2018-19 | $17.4 million |

| 2019-20 | $46.0 million |

| 2020-21 | $36.6 million |

| 2021-22 | $22.6 million |

| 2022-23 | $25.7 million |

| 2023-24 | $4.0 million |

Table 2 shows the estimated human resources used to deliver the two programs.

| Program | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGP demonstrationFootnote * | 1.23 | 2.07 | 2.28 | 1.67 | 2.07 |

| SGP deployment | 4.61 | 4.34 | 4.20 | 2.91 | 2.94 |

| ERPP | 4.96 | 7.03 | 5.89 | 2.91 | 2.00 |

Evaluation objectives, methods, and limitations

The evaluation examined the relevance and performance of the SGP and the ERPP from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2023. The evaluation used four lines of evidence (see Figure 6) to answer the following evaluation questions:

- Relevance:

- To what extent is there an ongoing and continued need for these two programs?

- To what extent do the priorities of the two programs align with federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes?

- Is there a legitimate and appropriate role for the federal government to play in supporting smart grid and emerging renewable power?

- Effectiveness (performance):

- How do the actual outputs and outcomes of the programs compared with targeted results?

- What internal and external factors impact (positively or negatively) the achievement of the intended outcomes?

- To what extent have there been unintended outcomes (positive or negative) resulting from the two programs?

- Efficiency (performance):

- To what extent have the two programs been designed (e.g., governance, delivery approach) in an efficient and economic manner to produce the intended outputs and achieving the intended outcomes?

- To what extent has each program been implemented as planned?

- To what extent has the program design been well executed including responsiveness to changing circumstances (e.g., COVID-19)?

- To what extent does each program collect performance information that supports the determination of effectiveness, efficiency, and economy?

- To what extent does each program consider Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) factors?

- Lessons learned:

- Was the “one window” approach of the Smart Grid Program accepting deployment, demonstration, and hybrid proposals, and signing agreements with hybrid projects effective at addressing industry needs? What worked well, what did not?

- How valuable are the Smart Grid Symposiums and other engagement products (e.g., project webpages, program website, brochure, etc.) in terms of achieving the set Canadian climate change and economic goals? What could be improved?

- What are other key lessons learned?

The approach and methodology used for the evaluation followed the TB Policy on Results (2016) and related Standards on Evaluation. It was also presented, reviewed, and endorsed by the EWG.

Figure 6: Lines of Evidence

|

Document Review |

Literature Review |

Key Informant (KI) Interviews |

Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over 200 internal documents (e.g., planning documents, program descriptions, regulatory frameworks, financial information on all 30 projects and 9 studies) and 34 external documents (e.g., websites containing strategic plans, budgets, collaboration agreements) were examined. | Academic literature, publications from governmental, international, and non-governmental organizations, grey literature, and media coverage were reviewed. Additionally, a comparative review that examined similar smart grid and renewable energy programming in other jurisdictions was undertaken. Seven programs were reviewed (see Appendix A). | A total of 28 KI interviews with 37 individuals were conducted via video conferencing: eight NRCan program delivery personnel, 22 funding recipients, two unsuccessful proponents, and five other stakeholders (e.g., academic institutions, provincial government, non-profit organization, and think tank representatives). Interview guides were tailored to the KI category interviewed to capture a range of perspectives by program and project type. | Six case studies (see Appendix B) were selected in consultation with senior program representatives and with the aim of establishing a diverse sample. Specific criteria included program, type of project, completion status, geographical region, completed or advance projects. For the case studies, key documents were reviewed (e.g., project descriptions, contribution agreements, progress and final reporting) and 12 additional KIs were interviewed (i.e., nine funding recipients, two program delivery personnel, one external stakeholder). |

Evaluation limitations

Although the evaluation was designed to collect data using multiple lines of evidence to enhance the reliability of results and validity of findings, the following limitations should be considered when reviewing the evaluation findings.

- Although available documents provided varying degrees of information that could be used to inform the evaluation, internal documents and documents provided by funding recipients had some gaps in actual outcomes and results. The evaluation team also observed that some outcome information is not captured in a consistent manner across projects. In particular, the evaluation team could not determine the progress of both programs towards the number of job years created due to inconsistent reporting and the discontinuing of annual reporting during the life of the projects for the ERPP and SGP deployment component. Therefore, the evaluation team could not “roll up” the information to report on the overall success of the projects in achieving the intended outcomes. This limitation was mitigated to the extent possible using other lines of evidence.

- The time available to assess the long-term outcomes of the SGP and ERPP was limited since contribution agreements were signed in 2018 or later. Therefore, the evaluation team ensured that the evaluation was properly focused on the programs’ achievement of the intended outputs, short-term outcomes, and medium-term outcomes.

- There was a challenge in securing interviews with unsuccessful proponents, academic institution representatives, provincial government representatives, and other stakeholders (e.g., non-profit organization and think tank representatives). Although the timeline for the interview period was extended, fewer than the originally desired number of interviews with these groups (n = 18) was completed (n = 7). This impacted the interpretation of some of the evaluation findings.

Relevance

Programs like the Smart Grid Program (SGP) and Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP) ERPP continue to be relevant, emphasizing the ongoing need for public investments in smart grids and emerging renewable energy projects

There is a continued need for public investments in demonstration and deployment of smart grids and deployment of emerging renewable energy projects. There is widespread agreement in the literature that transitioning to low-carbon energy is essential for meeting both global and national-level climate commitments, with investments in smart grids and renewable energy sources playing a key role in this transition. Furthermore, smart grid opportunities establish a business case for smart grid investments by demonstrating a high rate of return. While investments in renewable power are increasing around the world, the literature emphasizes the need for ongoing and increased investment in both well established and emerging renewable electricity sources. The importance of smart grids for managing the challenges associated with a higher reliance on variable and intermittent renewable energy sources is also widely recognized.

The SGP’s innovative approach in engaging electricity utilities as key adopters makes the SGP unique among programs geared towards power grid modernization in Canada. NRCan program delivery personnel highlighted that the SGP targets utilities and provides them the ability to innovate and experiment. This opportunity is not otherwise possible since utilities are almost entirely funded through the customer rate base and are economically regulated toward least-cost solutions which biases against innovation and grid modernization. NRCan program delivery personnel noted that as a result, increases in customer rates to finance innovation projects or projects targeting GHG outcomes are rarely approved by regulators, unless they also happen to be the least-cost solutions for ensuring safety and reliability. Therefore, the SGP is providing an opportunity to utilities to modernize electricity distribution and transmission to make grids more flexible and allow renewable energy to be connected to the grid that would otherwise not be prioritized or financed. One of the benefits for the utilities is the expected long-term cost reduction due to smart grids.

NRCan program delivery personnel also agreed that the ERPP served a unique purpose of funding emerging renewable energy technologies (e.g., geothermal, offshore wind, tidal) not yet proven in Canada that needed upfront capital funding. They further noted that the upfront capital funding de-risks these projects and makes them more viable for organizations to undertake. Previous NRCan renewable energy programs (e.g., ecoENERGY for Renewable Power) did not provide upfront funding, and therefore, did not focus on funding emerging renewable projects. This is not to imply that previous NRCan renewable energy programs were unsuccessful; they were just not designed to support emerging renewable projects.

Both the SGP and ERPP will not be renewed in their current form. However, the demonstration component of the SGP was renewed in Budget 2023 and rolled into the Energy Innovation Program, following the period of this review. The Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program (SREPs), now in place, extended and replaced aspects of the deployment component of the SGP and ERPP.

The SREPs is a GI program that provides up to $1.56 billion over eight years for projects centred on smart renewable energy and electrical grid modernization projects. The program aims to reduce GHG emissions by encouraging the replacement of fossil fuel-generated electricity with renewables that can provide essential grid services while supporting Canada’s equitable transition to an electrified economy.

Despite the SGP and ERPP's conclusion in their original program forms, the federal government's role in funding similar initiatives remains pertinent. The literature states that the GC plays a key role in supporting energy system transformation overall, as well as development and deployment of specific renewable and smart grid technologies. These technologies often require substantial upfront investments and long-term planning. Additionally, smart grid development and renewable energy deployment entail addressing complex regulatory, technical, and market challenges that necessitate government intervention and coordination. The GC involvement ensures that energy transition efforts prioritize environmental sustainability, energy security, and equitable access to clean energy resources, aligning with broader public interests and key commitments outlined in Canada’s evolving climate plans since 2015, including:

- The PCF, Canada’s first national climate plan developed in 2016;

- Canada’s strengthened climate plan, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy, developed in 2020;

- The provincial and territorial governments’ CES established in 2015; and

- The 2022-2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, which includes the goal of increasing Canadians’ access to clean energy.

Several non-governmental organizations, including Climate Institute Canada, the Canadian Electricity Association, the Pembina Institute, and the Institute for Sustainable Development, are calling on the Canadian government to increase direct funding of renewable energy infrastructure and smart grid innovation. Other countries (e.g., the United States [the US], Australia) have similarly recognized the role of the federal government in supporting and enabling grid modernization and energy system transformation.

NRCan program delivery personnel, funding recipients, and other stakeholders noted the importance of the continued role for the GC in supporting smart grid and emerging renewable power projects. For instance, it was indicated that if the GC continues to have clean energy and zero emissions goals, the GC should be providing support for these technologies and infrastructure for the country to meet those goals. Most funding recipients from both programs agreed that the NRCan funding was necessary for their projects to proceed. Finally, the NRCan program delivery personnel highlighted the strong uptake of NRCan’s more recently introduced SREPs as an indication of the continued need for smart grid and emerging renewable energy programming.

Other available programs complement the Smart Grid Program (SGP) and Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP)

With multiple sources calling for increased investment in renewable energy and smart grid capabilities and identifying a role for the GC in making these investments, literature indicates that duplication does not appear to be an identified concern or issue. The literature provided more of an indication of the potential for complementarity rather than duplication, considering the substantial size of overall investment estimated to be needed for the transition to a low-carbon energy system and the extent to which the SGP and ERPP currently work with other federal and provincial and territorial partners (e.g., by directly supporting provincial and territorial government initiatives). Even with its substantive investment, the SGP was only intended to benefit a relatively small number of stakeholders within the utilities sector. For example, it was noted that although the SGP received 86 proposals (of which 74 were deemed eligible) showing high interest in the program, the 22 funded SGP projects touched only a minimal number of the hundreds of utilities across Canada. To that end, interviewees noted a number of other federal and provincial programs that provide this complementary, additional, and needed funding support for SGP and ERPP projects, as well as funding programs that fund renewable energy projects that differ from those funded by the SGP and ERPP (e.g., projects at different stages of deployment). The programs highlighted were mainly federal government and provincial government programs (see Appendix C for the list of complementary programs reported by interviewees). Funding recipients have been able to pool funding from the SGP and ERPP and other sources together to support projects.

The programs align with federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes related to clean energy and climate change, but less so with those related to advancing reconciliation and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) goals

The SGP and ERPP harmonize with other initiatives in the larger Canadian ecosystem that intend to enhance smart grids and energy from renewable sources in Canada. The federal government has continued to make the transition to a clean growth economy and clean energy systems in Canada a priority. Furthermore, the synergy between renewable energy and smart grids enhances energy infrastructure resilience, a critical component for climate change adaptation. Renewable energy sources decrease GHG emissions while smart grids improve grid reliability and adaptability, effectively mitigating climate change impacts (e.g., extreme weather events). The SGP and ERPP, along with other similar programs and initiatives, are needed to support smart grids and renewable energy in Canada’s large and geographically diverse landscape.

As indicated in Figure 7, NRCan program delivery personnel and other stakeholders agreed that the SGP and ERPP are aligned with current federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes related to clean energy and climate change. However, NRCan program delivery personnel held mixed views regarding the SGP and ERPP’s alignment with current federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes related to advancing reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and meeting EDI goals. They noted that the programs did not prioritize EDI goals upon their inception, primarily because EDI was not a clearly defined policy at that time with no standard on how to implement it. While examples of Indigenous involvement in certain projects were provided (e.g., the Tu Deh-Kah Geothermal project is Indigenous owned), it was noted that Indigenous reconciliation and EDI are an area that needs improvement for future programs. Interviewees highlighted that SREPs is better focused on these priorities. The Energy Innovation Program (into which the Smart Grid Program Demonstration Renewal was integrated) has also increased and enhanced EDI criteria into its program calls.

Figure 7: Alignment with federal government priorities and NRCan strategic outcomes

The programs align with federal government priorities of:

- Increasing Canadians' access to clean energy

- Taking action on climate change and its impacts

The programs align less with federal government priorities of:

- Advancing reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and taking action to reduce inequality

The programs align with NRCan strategic priorities of:

- Accelerate development and adoption of clean technology to build a more resilient economy and transition to net-zero by 2050

- Create and maintain market access while improving competitiveness for Canada’s resource sectors

- Protect Canadians from the impacts of natural and human-induced hazards while supporting and advancing climate change adaptation

The programs align less with NRCan strategic priorities of:

- Advance reconciliation, strengthen relationships, increase engagement, and share economic benefits with Indigenous Peoples

- Promote, build, and foster equity, diversity and inclusion while supporting resource communities to thrive in a net-zero carbon economy

Effectiveness

Both programs have met all their immediate outcomes and some of their intermediate outcomes

Table 3 provides evidence that the SGP has met all its immediate outcomes. The first three outcomes were developed at the outset of the SGP, including the targets that were subsequently adjusted through amendments due to COVID-19- and regulatory decision-related delays. The last three immediate outcomes were expected outcomes of the SGP projects as stated in their Applicant Guide. No targets were set for these goals.

| Outcome | Indicator | Target | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased development and deployment of smart grid capabilities in Canada | Number of new or emerging smart grid integrated systems demonstrated or deployed | Two new or emerging smart grid integrated systems demonstrated or deployed by Q4 2022/23 |

Achieved

|

| Increased investment by stakeholders in smart grid technology demonstration and deployment projects | Ratio of investments made by stakeholders (e.g., provinces and industry), as compared to investments made by NRCan, in selected projects |

Demonstration – Project funding leveraged at an average of at least 1:1 Deployment – Project funding leveraged at an average of at least 1:3 |

Achieved

|

| Increased Canadian smart grid sector innovation | Number of utilities leading projects as a measure of the electricity sector’s capacity to implement innovative solutions with smart grid systems | 10 utilities supported through projects by Q4 2022/23 |

Achieved

|

| Number of new business models tested | Two new business models tested by Q4 2022/23 |

Achieved

|

|

| Increase electricity system reliability and resiliency, with maintained or enhanced cyber security |

Achieved

|

||

| Increase electricity system flexibility and increase renewable energy penetration |

Achieved

|

||

| Increase electricity system efficiency and use of existing electricity assets |

Achieved

|

||

Table 4 shows that two intermediate outcomes related to the smaller demonstration component of the program have been achieved. Overall, at the time of writing, the broader intermediate outcome for both deployment and demonstration has not yet been achieved.

| Outcome | Indicator | Target | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demonstration projects move emerging technologies closer to commercial readiness | Levels advanced based on Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale | Average TRL advanced by one level by Q4 2022/23 |

Achieved

|

| Increased number of commercially ready smart grid integrated systems from the demonstration program | Progress towards number of replications per technologies used in demonstration projects | At least one replication per technology demonstrated by 2026 |

Achieved

|

| Canadian smart grid sector growth and innovation | Progress towards number of job years of employment generated by projects | 4,500 direct and indirect job years of employment during the outcome period [from 2018/19 to 2028/29] from deployment projects and 700 direct and indirect job years of employment during the outcome period from demonstration projects |

In progress, but this target will not be achieved based on the data currently available.

|

| Number of new business cases established for regulatory approval | Two new business cases established for regulatory approval of future projects by Q4 2022/23 |

Not achieved

|

|

| Progress towards two new protocols, policies, codes, or standards developed with data from projects by 2028 | Two new protocols, policies, codes, or standards developed with data from projects by 2028 |

Achieved

|

KI interviews and the case studies provided additional information for most of the intermediate outcomes:

- Funding recipients provided examples of how the technologies developed and used in their projects could be replicated and scaled up, but this has not happened yet in most cases. Some funding recipients are also sharing the knowledge of their projects with other interested entities; other funding recipients noted barriers to scaling up, such as regulatory barriers.

- Direct evidence of the number of job years of employment generated by projects to date was limited and reported inconsistently, so a total for all projects cannot be established. Furthermore, while funding recipients were required to report on the number of job years created in their annual reports, annual reports were stopped for deployment projects after the fiscal year 2020-21 based on a recommendation made in the interest of reducing the reporting burden for funding recipients. It was noted by NRCan program delivery personnel that job information collected during the projects through the annual reports were only estimates, and that actuals are collected in their final reports at the end of projects. NRCan program delivery personnel also noted that their initial estimates were too high, and a more realistic target should have been set.

- According to NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients, many projects have demonstrated new business models, tested them successfully, and developed business cases for regulatory approval, but no evidence on the specific number of business cases established for regulatory approval was available. However, an example of a project testing a new business model and establishing a case for regulatory approval was the GridExchange project that tested a new compensation model for customers by providing reward tokens based on the value they provided to the energy grid. The reward tokens could then be redeemed at local businesses in exchange for goods and services. Getting regulatory approval continues to be a barrier to scaling-up projects.

- NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients highlighted that funding recipients have developed new knowledge from their projects and are more than willing to share that knowledge and the results from their projects with others directly and through industry events. In addition, each SGP case study project resulted in new knowledge being generated that informed the development of policies and protocols. For example, the Slemon Park project is the only example in PEI of renewable electricity generation being connected to a distribution circuit at a substation level. As such, PEI Energy Corporation is in the process of developing related operating protocols, codes, and standards.

Table 5 shows that the ERPP has achieved all immediate outcomes developed at the outset of the program.

| Outcome | Indicator | Target | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smaller (2-5 MW) emerging renewable power projects enabled by the program | Number of contribution agreements signed | Two contribution agreements signed by the end of 2019-20 |

Achieved

|

| Number of Regional Environmental Assessments (REAs) and Regional Energy Resource Assessments (RERAs) completed | Two REAs and/or RERAs completed and released to the public by the end of 2019-20 |

Achieved

|

|

| Larger portfolio of renewable energy technologies ready for commercialization in Canada | Number of different new emerging technologies with commercial-scale projects under development | Projects using at least two different technologies (one technology per project) are supported by the program by the end of 2019-20 |

Achieved

|

| Increased support by provinces for emerging renewable power deployment projects | Number of provincial support mechanisms put into place to complement the ERPP | Two provincially led support mechanisms (e.g., regulatory frameworks, power purchase agreements) enacted by the end of 2019-20 |

Achieved

|

Table 6 indicates two out of five ERPP intermediate outcomes have been achieved to date. It is important to note that the set date for these targets is in the future (i.e., 2025-26). The intermediate outcomes were developed at the outset of the ERPP, including the targets that were adjusted through amendments due to COVID-19- and regulatory decision-related delays.

| Outcome | Indicator | Target | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larger (5 MW+) emerging renewable power projects enabled by the program | Number of contribution agreements signed | Four contribution agreements signed by the end of 2021-22 |

Achieved

|

| Emerging renewable projects contributing to electricity grid | Progress towards number of projects commissioned | Four projects by the end of 2025-26 |

In progress but a lot of uncertainty regarding the likelihood of meeting this target.

|

| Progress towards increased renewable capacity from emerging renewable power projects | 150 megawatts (MW) of new electricity capacity supported by the end of 2025-26 |

In progress, but will not be achieved based on existing data.

|

|

| Progress towards increased electricity generation from emerging renewable projects | No target |

Uncertain

|

|

| Improved environmental performance through GHG reductions of Canadian electricity sector | Progress towards GHG emissions reductions attributable to emerging renewable power sources | One megatonne (MT) of direct GHG reductions annually by the end of 2026 |

In progress, but will not be achieved based on existing data.

|

| Increased employment in emerging renewables | Progress towards number of direct employment years associated with projects | A total of 12,000 direct job years by the end of 2025-26 |

In progress, but will not be achieved based on existing data.

|

| Increased investment by stakeholders in emerging renewable projects | Progress towards ratio of investments made by stakeholders (e.g., provinces and industry), as compared to investments made by NRCan in selected projects | 1:1 to 1:3 ($193 M from NRCan : $193 M to $579 M from other stakeholders), total from 2018-19 to 2025-26 |

Achieved

|

KI interviews and the case studies provided additional information for most of the intermediate outcomes:

- The Deep Earth Energy Production (DEEP) geothermal project in Saskatchewan is expected to be the next project to be commissioned (after Suffield Solar), with two other geothermal and two tidal projects ongoing. It is projected that these projects will be commissioned by March 2026. However, some projects are facing many provincial and federal regulatory barriers. NRCan program delivery personnel noted that discovering barriers and reducing and overcoming those barriers has been a common theme and has resulted in delays.

- The expected renewable capacity generated from the six ERPP projects is 71 MW, of which Suffield Solar is the biggest contributor at 23 MW (the only project commissioned thus far). The 71 MW will be below the estimated target of 150 MW to be generated for this outcome. The 150 MW target was established because the program was expected to fund another project that would result in 100 MW of renewable energy generation. However, barriers and a lack of interest from the provinces prevented the project from materializing.

- All deployment projects are expected to result in GHG emissions reductions by offsetting the use of fossil fuel energy with renewable energy. The expected reduction from all ERPP projects is 0.2 MT of CO2 emissions per year versus the target of 1.0 MT of CO2 emissions per year set at the start of the program.

- Direct evidence of the number of job years of employment created by ERPP projects to date was limited and reported inconsistently. Similar to SGP deployment, ERPP job data collected was inconsistent among projects and could not be rolled up, and annual reports stopped being required for ERPP projects after the fiscal year 2020-21. It was noted by NRCan program delivery personnel that job information collected during the projects through the annual reports were only estimates, and that actuals are collected in their final reports at the end of projects. The program has recently recognized this challenge, and started to modify its process, to improve collection of job data.

Both Smart Grid Program (SGP) and Emerging Renewable Power Program (ERPP) appear to be on track to partially achieve their long-term outcomes

Both programs have some intermediate outcomes that have not been achieved to date and are facing barriers that may limit their ability to fully achieve their long-term outcomes and related targets. For the SGP, regulatory barriers are the main challenge the program is facing in achieving its long-term outcomes of “Environmental benefits from smart grid development and deployment” and “Economic benefits from smart grid projects.” NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients expected the SGP projects to yield economic benefits in the form of cost-saving opportunities for customers. The modernized grids provide more reliable services for residential and industrial customers, reducing both the frequency and duration of disruptions. This leads to lower rates and other opportunities for additional savings from DERs, solar panel installations, smart hot water heater installations, and so forth. Other expected socio-economic benefits include increased tourism in communities with these technologies; improved connections between utilities and communities (fostering spinoff opportunities such as downtown revitalization); and workforce development through staff and student training via the projects. However, the regulatory barriers will limit or delay additional and expanded smart grid projects. The SGP has not fully achieved its intermediate outcome of “Canadian smart grid sector growth and innovation” as the program has experienced challenges with establishing new business cases for regulatory approval. Furthermore, it remains unclear to what extent the program has generated employment. However, there are a number of SGP projects that have been successful and will likely contribute to the long-term outcomes.

The barriers faced by some projects suggests that the program is not going to meet a number of its intermediate outcomes (e.g., “Emerging Renewable projects contributing to electricity grid” and “Improved environmental performance through GHG reductions of Canadian electricity sector”) and related targets. This will limit the ERPP’s achievement of its long-term outcomes of “Expanded portfolio of commercially viable renewable energy technologies available in Canada” and “Establishment of new industries and supply chains” and related targets.

Furthermore, it remains unclear to what extent the program has generated employment. Regardless, according to NRCan delivery personnel and funding recipients, the ERPP projects are expected to bring socio-economic benefits to the communities in which they are built, including enhanced electricity generation security and plant construction; facilitated worker repurposing (e.g., transitioning oil and gas workers to the geothermal industry); utilization of existing equipment (e.g., repurposing fishing boats for deploying instrumentation buoys in tidal projects); future spinoff projects for the funded organizations; lithium extraction from geothermal projects; brine salt for road maintenance; and expansion of the local service industry (e.g., through increased patronage of local restaurants and hotels by project staff and their families). Additionally, the ERPP studies are expected to yield direct and indirect long-term socio-economic benefits through knowledge dissemination, such as findings to benefit other groups (e.g., providing fishers with the fish atlas developed from the tidal study); creation of new toolkits for policy-makers; and development of new inventories of expertise and dialogue in specific areas and communities. While long-term outcomes remain positive for certain projects, others are encountering challenges.

Due to the aforementioned limitations and various external factors, both programs may not meet their targets in contributing to the ultimate outcome of “Provide Canadians with access to safe, resilient, reliable, affordable, and non-emitting energy, leading to net-zero emissions in the electricity sector” However, it is important to note that the SGP and ERPP are just two of many programs and initiatives contributing to the ultimate outcome.

A number of positive unintended outcomes were identified

Positive unintended outcomes of the programs were mainly technological or project-specific. For both programs, some projects were able to go beyond initial expectations and result in the positive unintended outcomes depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Positive unintended outcomes from case study projects

SGP

- Awards and recognition

- International investment

- Higher than expected customer engagement/interest

- Applying the learnings from the projects to other areas of the organization

ERPP

- Additional research opportunities

- Supporting EDI and EDI hiring practices

The high level of program flexibility, professionalism of NRCan program staff, and dissemination of program information and results are key to success

The high level of flexibility in the program design and NRCan program staff in adapting to changing circumstances are key positive factors. NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients complimented the ability of the SGP and ERPP to be flexible (within allowable parameters) regarding payments and project timelines in the face of changing circumstances. These features allow the redirection of funding and/or non-repayable contributions. For example, program documentation showed that the ERPP allows both non-repayable contribution agreements for ongoing projects, which were originally subject to repayable agreements within the first five years of operation and front-end loading of allocated funds for projects that face technical or regulatory risks. The SGP offers flexible funding for some types of eligible expenditures (e.g., overhead expenditures and travel expenditures). Other miscellaneous expenditures, such as printing services and laboratory and field supplies, may be eligible for flexibility measures where funding may be redirected in response to changing or unanticipated circumstances surrounding the project. Further, the programs are able to accommodate additional flexibility measures requested by Indigenous proponents. Funding recipients also highlighted the professionalism of the staff at NRCan in working with them to ensure project success by being flexible and heavily involved in the projects when needed. Similar future programming could benefit from implementation of these program features.

The evaluation found the widespread sharing of program information and results to intended audiences and the broader public is a factor that has positively influenced the programs.

- Funding recipients highlighted numerous benefits of NRCan’s Smart Grid Symposium (see text box), including sharing and giving their projects visibility, gaining insight into broader developments across Canada, and understanding the different challenges and barriers projects are facing. The funding recipients were keen on the Smart Grid Symposium continuing for the continuous sharing of knowledge and ideas. Funding recipients suggested inviting regulators to the annual Smart Grid Symposium to allow participants to engage regulators and help them learn about the projects, expected outcomes, and what they need to be able to scale up. Funding recipients emphasized that engaging regulators earlier would shorten lead times for the project and facilitate regulatory change to enable project scaling up.

The Smart Grid Symposium held in October 2019 was the culmination of a series of stakeholder engagement activities whose main objective was to shape the new SGP that was announced in Budget 2017. The symposium displayed projects that had been selected to be part of the SGP, promoted knowledge sharing across the electricity industry, and ultimately contributed to NRCan’s capacity to design and manage its future programs. The 117 attendees were primarily stakeholders from utility companies. The Smart Grid Symposium has been held annually starting in 2020, the symposiums were held virtually until the most recent in April 2024.

- Interested stakeholders and others can access updated information on the SGP webpage, including information on background and rationale for smart grids and a list of currently funded projects with accompanying links to project websites. The program brochure can also be accessed from the SGP webpage, as well as more detailed documents and reports such as the most recent (2020-21) Smart Grid in Canada report.

- Stakeholders with an interest in emerging renewable power can access the ERPP webpage, which provides a description and rationale for the program, regularly updated project announcements, and a detailed frequently asked question page for funding applicants. Other communications, including emerging renewable power issue updates and industry perspectives reports and presentations (such as a November 2021 Geothermal overview presentation which included industry perspectives), have contributed to knowledge sharing among stakeholders and potential program funding applicants. In addition to these engagement products, NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients referred to the public announcements for projects funded by the ERPP, highlighting the DEEP project in Saskatchewan where the Prime Minister made the announcement.

- Other communications, such as industry perspectives reports, have also contributed to raising stakeholder awareness of both programs and current issues in smart grid technology in Canada or abroad.

NRCan program delivery personnel noted wanting to do more for sharing and showcasing project results across funding recipients, within government, to other interested stakeholders, and with the public through case studies and other things of that nature. However, they also noted the need for additional support to be able to undertake such activities. The importance of widespread sharing of program information and results was also supported by the review of programs from other jurisdictions (e.g., US Department of Energy’s Smart Grid Grants (SGG), Grid Modernization Initiative). In particular, the widespread public sharing of program information is expected to reduce investment uncertainty for decision-makers and guide future investments in grid modernization.

Interviews and internal NRCan documentation also provided additional factors that have positively influenced both programs:

- Program funding – Funding recipients from both programs highlighted the importance of the SGP and ERPP funding to de-risk their projects and ultimately allowed them to proceed.

- Partnerships/engagement from stakeholders and communities in projects – NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients from both programs highlighted the importance of buy-in and engagement of stakeholders from various levels for the success of individual projects and the programs. This included buy-in from senior management within NRCan and the GC to support renewable energy projects (including attending announcements), senior management and leadership within the funded organizations, and project partners (e.g., other federal departments, and provincial governments) helping support the project and engage with relevant stakeholders. However, this was also noted as a challenge by some funding recipients as getting everyone “on board” for some of the projects resulted in project delays.

- Policy landscape in Canada and increased public interest and investments in smart grids and renewable energy – Given the GC and the world’s increased commitments and interest in addressing climate change, an NRCan program delivery personnel and funding recipients indicated there is increased interest and uptake of similar programs. A stakeholder also noted the increased public interest in these programs due to energy insecurity related to world events, such as global price fluctuations.

The environmental scan completed as part of the literature review also identified factors that positively impact programs with similar design. Mainly, the final report for the US Department of Energy’s SGG identified program elements contributing to success that apply to the SGP (and less directly, the ERPP):

- The program’s 50% cost-share requirement led to successful leveraging of investment from private or local sources to supplement or add to the investment of public funds.

- The program’s focus on new technologies (i.e., supporting utilities in implementing them) was credited with helping to mature the smart grid vendor marketplace, with positive impacts on job creation.

Regulatory-, technological-, and COVID-19-related issues experienced by projects have negatively influenced both program implementation and outcome achievement

Regulatory barriers have been identified as a key negative factor that influenced both programs. Federal and provincial regulations pose significant constraints on the progression of projects, even extending to post-completion stages, especially for SGP projects. For example, the GridExchange project was described as being “stuck” after the pilot stage and unable to secure funding to scale-up and achieve regulatory support. Likewise, the need to obtain regulatory approvals given potential risks to the environment are limiting the progress of some projects supported by the ERPP. Profits on some ERPP projects can be further delayed due to regulatory risks, leading to financial difficulties for funding recipients. While some KIs highlighted the involvement of the provincial government in projects as a positive, it was noted that some provincial goals and priorities do not align with federal goals and priorities. This resulted in organizations facing challenges in scaling up projects following receipt of federal funding, as well as project delays or cancellation. Conflicting federal and provincial priorities can create tensions that undermine the objectives of the programs, potentially diminishing their impact on Canada's progress towards its climate targets.

NRCan program delivery personnel, funding recipients, and other stakeholders suggested that NRCan could provide more support in examining the impact of a regulatory environment on possible business models and constraints that can impose on applying or scaling new technologies. For instance, funding recipients suggested that funding is needed to continue to move projects past the next level of barriers to scale, including past the barriers imposed by regulation. Indeed, the programs have taken action to reduce the negative impact of regulatory barriers on projects, including front-loading of allocated funds for emerging renewable power projects that face higher levels of regulatory risks, the creation of the 2023 Tidal Energy Task Force and the OERD’s Innovation and Electricity Regulatory Initiative, and the introduction of SREPs. However, further and continued work on the regulatory and provincial and federal government barriers that are impacting projects during their lifecycle is needed as several projects still face unexpected regulatory barriers. NRCan program delivery personnel should and intend to continue to ensure mechanisms are in place so that these issues are addressed as early as possible.